A few months ago, I suggested that we had entered a state of federal student loan permafrost, a tenuous but seemingly endless halt on repayment coupled with ongoing, targeted batches of loan forgiveness. That condition shows new signs of remaining, with the Wall Street Journal reporting last week that the U.S. Department of Education told loan servicers not to start sending billing statements to borrowers, indicating repayments will not resume after August 31, the day the Biden administration had chosen for the end of the current freeze extension.

This has become an almost comical state of affairs, except that the freeze is not really a freeze, which would have had repayments pick back up as if nothing had happened when the freeze ended. No, during this “freeze” interest payments have been set at zero, not simply held in stasis to be paid when the freeze ends. Also, the frozen months count toward various types of time‐based loan forgiveness. That’s why the freeze has so far cost taxpayers well beyond $100 billion.

Of course, this might just be the student loan sideshow if the Biden administration declares some level of blanket forgiveness. Some senators have called for cancelation of up to $50,000 per borrower, but the Biden administration, according to reports, is looking at $10,000, maybe with income limits.

Setting aside the huge constitutional problem with such cancelation – the Constitution gives the president no authority to forgive hundreds‐of‐billions in debt – it would be very poorly targeted to those in need. Keep in mind that people with college degrees tended to weather the COVID economy much better than those without; less than 38 percent of American adults have bachelor’s degrees; student loans are disproportionately used by people to attend graduate school; and that higher ed confers big earnings premiums.

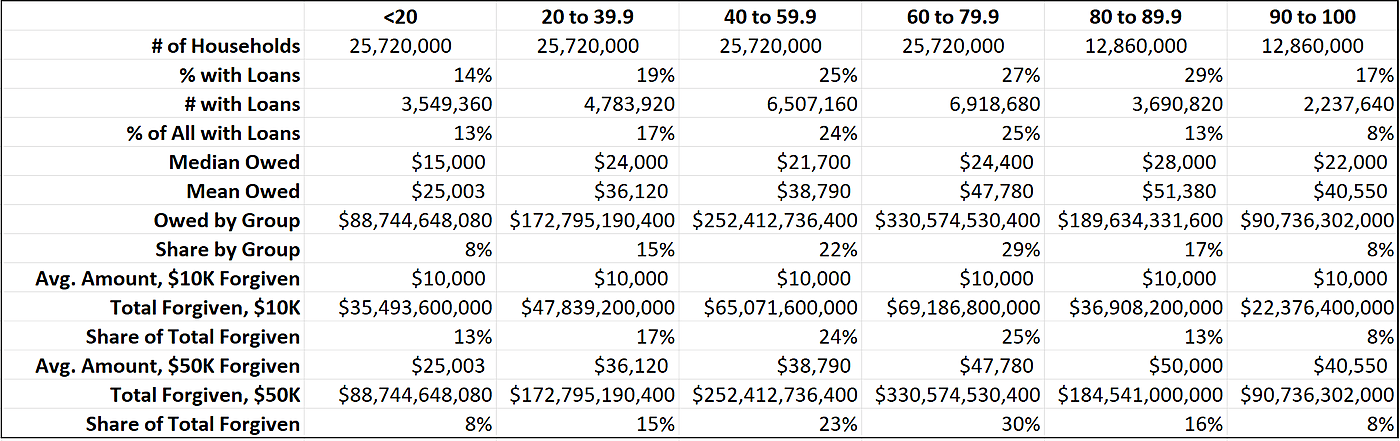

To spell it out a bit more, using various data sources I have estimated distribution of cancelation based on income and race, both of which have been pointed to as reasons for forgiveness. As shown below, with $10,000 canceled, 21 percent would go to the top quintile (divided into the top two deciles) of households by income, and only 13 percent to the lowest quintile. The top two quintiles would receive nearly half of all cancelation. $50,000 cancelation would be even more skewed, with the top quintile getting 24 percent of the total and the bottom only 8 percent. That’s because wealthier people tend to consume more – and more expensive – education.

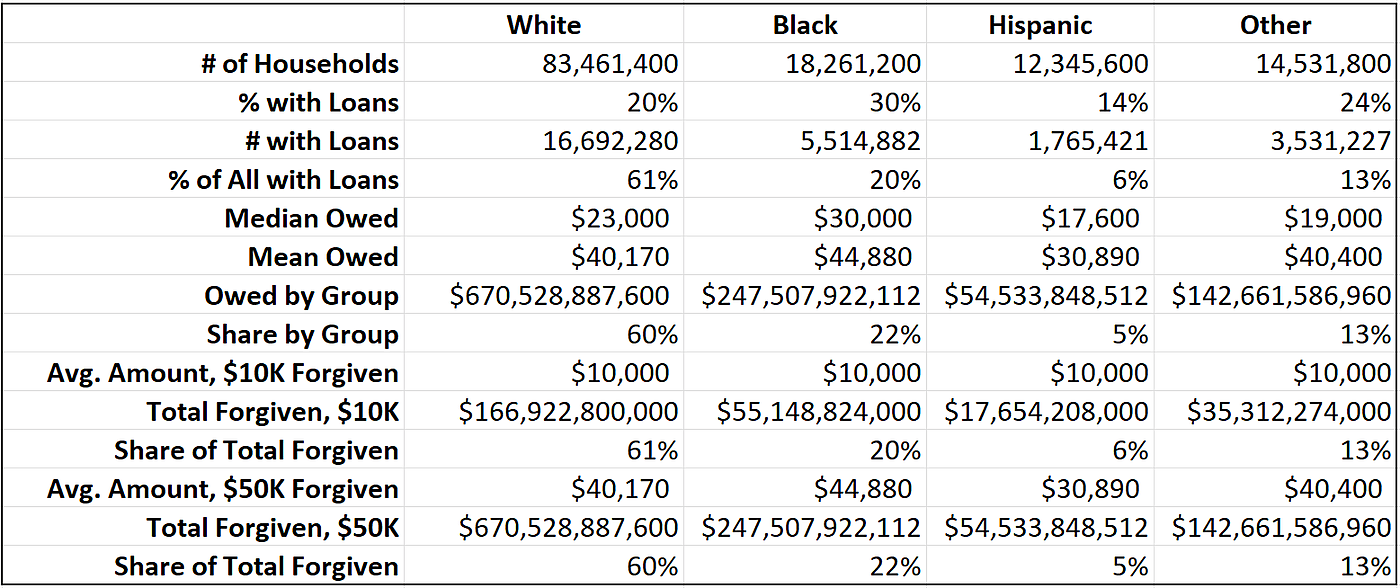

The race‐based argument for mass cancelation is that African‐American students tend to take on more debt for college than white students. That is accurate, but mass cancelation would still be poorly targeted because there are so many more non‐black students. With $10,000, African Americans would get 20 percent of total canceled debt and white borrowers 61 percent. Only 6 percent would go to Hispanic households, which tend to consume less higher education, and 13 percent to “other,” including Asians who tend to consume more higher education than other groups. At $50,000, the white share drops to 60 percent and African‐American to 22 percent, while the Hispanic share drops 1 percentage point, and other stays the same.

One final argument is that debt cancelation would disproportionately help people with low wealth, and when one looks at current wealth it appears to do that. But as Adam Looney of the Brookings Institution explains, once the value of the education is accounted for, cancelation skews toward the wealthy. And you must consider that value: As Looney notes, assessing student debt without considering the value of the education is like looking at a mortgage without considering the value of the house.

No matter where one stands on cancelation, it is hard to believe that anyone is satisfied with the current can‐kicking. There is simply no rational excuse for extending the freeze again. But there is also no justification for mass cancelation. Which might be why we are stuck in permafrost: Telling borrowers it is time give taxpayers their money back is hard politically. But it is the right thing to do.

This Cato Institute article was republished with permission.