There are few issues left in Washington, DC on which both parties can agree. Yet increasingly the push to regulate “Big Tech” is an area of agreement for Republicans and Democrats.

This consensus was on full display at last week’s contentious congressional hearing featuring top tech CEOs such as Google’s Sundar Pichai, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Apple’s Tim Cook, and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg.

"This hearing has made one fact clear to me," Democratic Rep. David Cicilline said. "These companies as they exist today have monopoly power. Some need to be broken up, all need to be properly regulated and held accountable. We need to ensure the antitrust laws, first written more than a century ago, work in the digital age."

This is seemingly the mainstream position among today’s Democrats. The party’s presidential nominee, Joe Biden, has backed restoring heavy-handed internet regulations known as “net neutrality” and is also encouraging the federal government to wade into the debate over social media censorship by repealing Section 230, which shields online platforms for liability for what users post. (Social media as we know it couldn’t exist without Section 230.)

Meanwhile, many prominent Republicans and conservatives have also come out in favor of regulating Big Tech.

Populist Republican Sen. Josh Hawley has called for regulating tech companies' ability to moderate their own platforms, and argued that “Google and Facebook should not be a law unto themselves.” The Missouri senator has also introduced legislation that would impose nanny-state restrictions on social media to combat perceived addiction. Hawley’s bill would ban popular features such as Snapchat “streaks” and YouTube autoplay.

While many principled small-government conservatives, such as Sen. Rand Paul, still back a free-market approach to tech policy issues, Hawley is not an outlier by any means.

Conservative anger at Big Tech’s censorship should not delude us into supporting the Big Government tool of antitrust. https://t.co/bLZiQ7t1sr

— Senator Rand Paul (@RandPaul) August 3, 2020

Indeed, President Trump has also backed the regulation of social media companies to combat perceived anti-conservative bias. And the most popular conservative media personality in the country, Fox News host Tucker Carlson, regularly rails against Big Tech—even agreeing with progressive proposals to use the heavy hand of government antitrust regulation to break up companies such as Facebook and Google.

So, if major figures from both parties can agree on regulating Big Tech, it must be a good idea, right? Not so fast.

From left to right, the intentions behind these regulatory proposals are often good. After all, most reasonable people would likely share Democrats’ desire to see Big Tech better handle misinformation, “fake news,” and foreign election interference, while conservative Republicans’ calls for political neutrality online are no doubt appealing in the abstract.

Unfortunately, in their haphazard rush to score political points through government action, would-be regulators from both parties are forgetting the inevitable “knowledge problem” that plagues any central planners who try to dictate the minutiae of complicated industries from the halls of Washington, DC.

Economic philosopher Friedrich A. Hayek diagnosed this fatal flaw of government control in his seminal work "The Use of Knowledge in Society."

“If we can agree that the economic problem of society is mainly one of rapid adaptation to changes in the particular circumstances of time and place,” Hayek wrote. “It would seem to follow that the ultimate decisions must be left to the people who are familiar with these circumstances, who know directly of the relevant changes and of the resources immediately available to meet them.”

“We cannot expect that this problem will be solved by first communicating all this knowledge to a central board which, after integrating all knowledge, issues its orders,” he continued. “We must solve it by some form of decentralization. But this answers only part of our problem. We need decentralization because only thus can we insure that the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place will be promptly used.”

To put it simply, the knowledge problem means that centralized decision-making is doomed to failure, because only those closest to a given situation have the relevant knowledge and awareness to properly gauge the best outcome. For example, a planning committee of bureaucrats in Washington, DC that tried to set the prices for corn sales in Iowa is far less likely to set an efficient and realistic price than if farmers themselves can respond to changes in their business and adjust their own prices accordingly.

“The knowledge problem... is about more than the ability to plan an economy,” Jeffrey A. Tucker wrote in his analysis of Hayek’s theory. “It is about the whole of our lives. It is about the ability to plan and direct the course of civilization. That capacity to manage the world, even the smallest part of it, will always and everywhere elude our grasp.”

The knowledge problem plagues all centralized government planning. But the gap between the knowledge of the often elderly members of Congress who would write Big Tech regulatory legislation and the extremely advanced and complex workings of the tech industry is especially acute.

Consider a viral moment from a 2018 hearing where Zuckerberg testified before the Senate and was asked a hilarious question by former Sen. Orrin Hatch, who was 84 years old at the time.

“How do you sustain a business model in which users don’t pay for your service?” Hatch asked the Facebook CEO.

Holding back a laugh, Zuckerberg replied “Senator… we run ads.”

Sen. Hatch: "If [a version of Facebook will always be free], how do you sustain a business model in which users don't pay for your service?"

— CBS News (@CBSNews) April 10, 2018

Mark Zuckerberg: "Senator, we run ads." https://t.co/CbFO899XlU pic.twitter.com/bGKWks7zIk

Given the fact that he was born in 1934, we can certainly forgive former Sen. Hatch for not grasping the workings of Facebook. But the lighthearted example of a top Republican senator’s total failure to grasp the basics of social media 101 should be a giant red flag. If some of Congress’s most prominent members can’t even understand the basics of social media, how are they supposed to regulate the industry with even a modicum of competence?

It’s not as if Hatch was alone in his tech illiteracy. The average age in the US Senate is 63 years old. Do you think your grandma or grandpa would fare any better if asked to write the rules for Google or Facebook?

The House of Representatives fares somewhat better, with an average age of 58 years old. But last week’s hearing showed us many members of the House are just as plagued by tech illiteracy as their colleagues in the Senate.

Rep. Greg Steube of Florida used some of his time questioning Pichai, the Google CEO, to ask why some of his campaign emails go to his parents' “spam” folders on Gmail. Yes, seriously.

Rep. Steube complains to Google CEO about his campaign emails going to Gmail spam boxes and says that it's only happening to republicans. (No, pretty much every campaign deals with email delivery issues.) pic.twitter.com/XH1floO9ff

— Tony Webster (@webster) July 29, 2020

In another hilarious-yet-eyebrow-raising turn of events, Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner confronted Mark Zuckerberg on the censorship of Donald Trump Jr.’s Twitter posts on the controversial drug hydroxychloroquine that some tout as a COVID-19 treatment.

It does not inspire great confidence in the government's ability to fairly regulate Big Tech when members of Congress accuse the wrong company of censoring Don Trump Jr. https://t.co/PIGgPFpFYe

— Robby Soave (@robbysoave) July 29, 2020

The only problem? Zuckerberg is the CEO of Facebook—not Twitter.

Meanwhile, Biden would be the oldest president ever if elected, while at the same time he promises to launch a government overhaul of the internet as we know it. If you’re looking for insights into Biden’s tech acumen, consider an answer he provided to a debate-stage question… about race:

Social workers help parents deal with how to raise their children. It’s not that they don’t want to help, they don’t know what to play the radio, make sure the television — excuse me, make sure you have the record player on at night, the — make sure that kids hear words, a kid coming from a very poor school — a very poor background will hear 4 million words fewer spoken by the time we get there.

Does anyone really think an aging septuagenarian who struggles to form full sentences and thinks people still use “record players” should write the rules for Silicon Valley?

It’s perfectly fine to laugh at these moments and flubs. We could use more light-heartedness in our politics. But we can’t overlook the crucial lesson here as well.

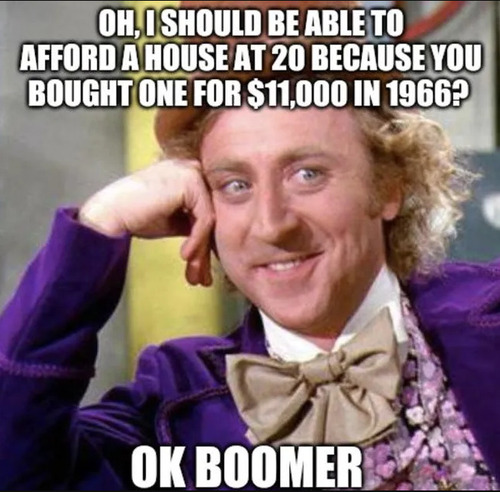

Young people have made a generational rallying cry out of the slogan “OK Boomer,” through millions of memes and social media posts poking fun at older generations’ inability to understand new societal realities. While sometimes applied flippantly or rudely, at its best “OK Boomer” is a lighthearted way of pointing out the Hayekian knowledge problem older folks run into when they lecture young people on how to navigate new, unfamiliar complexities.

"I paid for my college by myself by waiting tables, young people these days are just lazy."

“Ok Boomer.” Actually, adjusting for inflation, the price of college tuition has roughly tripled since 1980. (Thanks, government subsidies!)

And so on. You get the point.

There is no more glaring issue where the “OK Boomer” mantra’s invocation of the knowledge problem is more relevant than the debate over regulating Big Tech. Our elderly leaders in Congress have made it clear they don’t even understand the basic revenue model of social media, aren’t familiar with how email filtering works, and fail to grasp the differences between various online platforms.

If we put well-intentioned but aged politicians in charge of writing the rules, their lack of knowledge and familiarity with technology would result in deeply flawed and broken regulations. How can you write a bill effectively regulating speech on social media if you don’t understand the difference between Facebook and Twitter? It seems almost certain such regulatory attempts would end with rules misapplied and innovation throttled.

And no, this doesn’t mean it’s fine for young legislators like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to regulate Big Tech however they want. Even the most youthful, tech-savvy politicians will be prone to the knowledge problem, because they don’t have the familiarity, expertise, or skin-in-the-game of an on-the-ground entrepreneur. But the age issue no doubt exacerbates this problem.

Major disruptions to the technology we use every day will inevitably accompany any serious effort by Boomers in Congress to regulate an industry they can’t even comprehend. That’s a fate we should all want to avoid.