1. The top 1 percent are getting all the income growth while the middle class is stagnating

A paper published in 2003 by economists Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez reported that the over the last few decades, the share of total income going to the top 1 percent doubled while middle-class incomes declined by 8 percent. These findings have been cited repeatedly as proof that American-style capitalism is a failure.

However, measuring middle-class incomes, as well as the incomes of the top 1 percent, is a difficult task. There are significant opportunities for measurement error, disagreement as to what should be considered income, which measure to use to adjust incomes for inflation, and so on.

Over time, more research has come out that has improved upon the original Piketty and Saez (2003) methodology and provided better estimates of the evolution of income inequality in America. These studies, such as Auten and Splinter (2018), Larrimore et al. (2017), and Bricker et al. (2016), all show that income inequality has grown far less than originally estimated by Piketty and Saez, usually half as much or less.

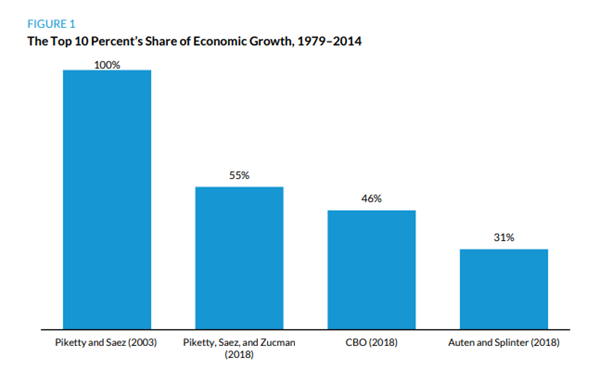

The Urban Institute, a DC think tank, has also demonstrated (see Figure 1) that contrary to the methods of Piketty and Saez (2003), which would imply that all the income growth since 1979 has gone to the top 10 percent, recent estimates show vastly lower estimates of unequal economic progress.

And in contrast to the idea of stagnating Middle America, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) finds that the bottom 80 percent of the income distribution (i.e. the poor and middle class) saw their incomes grow by 32 percent between 1980 and 2015. After accounting for progressive taxation and transfer payments to households, such as social security payments, the middle-income quintiles (i.e. the middle class) and the bottom-income quintile (i.e. the poor) saw their incomes grow by 46 and 79 percent respectively.

2. The top 1 percent are lazy capitalists who live lavishly because of their past investments or inheritances

It turns out this may be more of a stereotype than an actual truism. Using data from millions of businesses and their owners, economists from the US Treasury and the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) recently explored the nature of top income earners in the US between 2001 and 2014.

Contrary to the common populist fat cat narrative, “top earners are predominantly working rich, and the majority of top income accrues to…wage earners and entrepreneurs, not idle owners of financial and physical capital.” According to this research, “entrepreneurs who actively manage their firms are key for top income inequality.”

Digging further into the data, it is revealed that the typical business owned by someone in the top 1 – 0.1 percent of income earners is a single-establishment firm in professional services.

Digging further into the data, it is revealed that the typical business owned by someone in the top 1 – 0.1 percent of income earners is a single-establishment firm in professional services (e.g., lawyers and consultants) or health services (e.g., physicians and dentists). On top of this, they found that “at least 75%” of top income earners, including millionaires, are self-made.

If anyone were to doubt the value of the work done by these very rich individuals, consider that the economists found that private business profit falls by an astounding 75 percent after the owner dies or retires.

3. Rising inequality is primarily driven by CEOs getting paid more and workers less

No doubt this occurs to an extent, but it doesn’t capture the whole picture of inequality in America. In an intriguing paper titled “Firming Up Inequality,” economists from the Social Security Administration and NBER illuminate the role firms play in the evolution of inequality.

Using a massive dataset that covers tens of millions of employees and employers, the economists demonstrate that within the same firms, income inequality doesn’t grow nearly as much as it does between different firms.

In other words, income inequality is not so much a function of the average worker at Wal-Mart seeing stagnant wages while the CEO gets richer and richer. Rather, it is more a result of a business—for example, a law firm—paying higher wages and having faster-growing wages on average in comparison to another that pays comparatively low wages with little wage growth, say, a fast-food chain.

The economists find that between 1981 and 2013, two-thirds of the rise in earnings inequality is attributable to the rise in inequality between firms, and around one-third is a result of the rise in inequality within firms.

The economists find that between 1981 and 2013, two-thirds of the rise in earnings inequality is attributable to the rise in inequality between firms, and around one-third is a result of the rise in inequality within firms.

According to the data, among companies with more than 10,000 workers, the top 50 highest paid employees (including the CEO and other senior executives) have had their earnings growth far outpace the average employees, likely due to how executive compensation is increasingly tied to the stock market.

However, rising top executive compensation at large firms accounts for a mere 3 percent of the increase in income inequality within the firms they belong to. Why? Well, since “they make up a very small share of employment—accounting for only 35,000 of the 20 million employees in mega-firms…rising top executive earnings explain little of the increase in the variance in overall earnings (i.e. income inequality),” the authors note.

Conclusion

In a time where politicians are calling for 70 percent marginal tax rates on the wealthy to reduce allegedly catastrophic levels of income inequality, it’s worth asking if the premises upon which the argument for confiscatory taxation are based are solid.

If the wealthy are entrepreneurs rather than fat cats, confiscatory taxation may discourage innovativeness rather than anti-social rent-seeking.

If the wealthy aren’t gobbling up all the economy’s income, the case for confiscatory taxation is lesser. If the wealthy are entrepreneurs rather than fat cats, confiscatory taxation may discourage innovativeness rather than anti-social rent-seeking. And if inequality is not so much driven by CEO pay and is more predominantly caused by some businesses (and all the employees within the business) doing better than others, then perhaps it can be addressed in a more effective way that doesn’t involve collectively punishing people for being successful.